Film Essay: Top Ten Lists Reflections: Part 3: Mainstay Directors

Directors who made the list

One of the great joys watching movies over the past couple of decades has been seeing directors who continue to re-invent themselves. Directors who challenge themselves in the genres they make, the style in which they make movies, and especially directors who don’t play it safe, pushing the boundaries of cinema. Seeing the revival of Terrence Mallick’s career beginning with The Thin Red Line in 1998 and continuing through the hypnotic and maddening Knight of Cups, it is amazing to think that this great director did not make a film from 1978-1997.

Surveying my selections for the best films of each year, I do not find it surprising that the director who has the most films on this list is Martin Scorsese (Gangs of New York, The Aviator, The Departed, Hugo, The Wolf of Wallstreet, and Silence).

With six films, Scorsese appears just slightly more than once every three years. That is a remarkable number of films being made (nothing compared to Woody Allen’s output, but no one has that level of output), let alone capturing my attention and love. Even his films that I didn’t like at the time (Bringing out the Dead) have tended to grow in my estimation. Really, the only film that he has made that has decreased in my mind, Gangs of New York, still has flourishes of stylistic genius, whether the use of fast motion during the fights or the intensely calm scene with Daniel Day Lewis’ superb acting as Bill the Butcher, delivering the monologue about how he cut out his own eye while wearing the American flag. The prejudice and hatred of the Nativists also seem more relevant today than they did in 2002.

In surveying the other directors to receive multiple films on my lists, there are “two” others who have nabbed 5 slots each from 1998-2019. I am not shocked that Charlie Kaufman both as a director (twice) and a screenwriter (three other films) has made the list 5 times; but, the person who does shock me (because if you asked me to name the best directors currently working, his name would not rise to the top of my list) is Mike Leigh. It’s interesting that his name doesn’t come to my mind when I think of the great directors working. It should.

Below is a consideration of a couple directors who have made my list multiple times. There will be a separate reflection on “new and emerging directors” during my lifetime.

Martin Scorsese:

Of the generation of filmmakers known as the Film Brats, Martin Scorsese continues to innovate and push the boundaries of cinema unlike any of his peers, even the father of the film brats, Francis Ford Coppola. Prior to the passing of Robert Altman, I think you could have an actual debate about who is the greatest living director. With Robert Altman’s passing in 2006, I no longer think there is a legitimate debate. There is only one answer. Martin Scorsese.

Unlike his peer, Steven Speilberg, who continues to create great films, but often falls back on the same techniques and style that has served him so well in the past, Scorsese, for like a better phrase, continues to reinvent himself. The times that Steven does stretch himself, Minority Report or Munich, demonstrate his incredible abilities, but, he often doesn’t use those talents and instead settles for cinematic cliché that gives us films like Rin Tin Tin or War of the Worlds or BIG. Scorsese on the other hand has moved from not only making films about anti-heroes (Taxi Driver, Mean Streets, Casino, Goodfellas to name a few) to crafting religious films (The Last Temptation of Christ, Silence, and the unsuccessful Kundun), to pure genre pics (Shutter Island, The Departed) to even a family film (Hugo). In these changes, he has also continues to innovate the way he approaches cinema. Let’s look at a few specific examples:

Taxi Driver

In Taxi Driver, Scorsese began to solidify his use of slow motion in POVs. Prior to his films, slow motion, in cinematic language, generally was used to create an increase in tension, to slow the action down, in order for the audience to better appreciate the importance of the moment. But, Scorsese would choose instead to speed up action scenes that normally would be in slow motion. Like the bar fight in Mean Streets, it plays at hyper-pace, placing us in the scene and experiencing the adrenaline rush of such a fight. In Taxi Driver, Scorsese begins to play with using slow motion in POV shots to place us inside the mind of the character. Watch how every time there is a black person on screen, Travis Bickle’s POV shots slow down. Scorsese visually is showing us how a racist looks at the world, always aware of the black people and making sure to keep an eye on them.

Also watch how Scorsese subtly and subconsciously makes us a part of his pictures. In one of the opening shots in Taxi Driver, Travis looks around the taxi bay and the camera begins an almost 360 degree pan of the bay, but when it returns to Travis, whom we assume we are in his point of view, he is leaving. We realize that it was the audience who was looking around the bay as Travis has more important things to do. This makes his films feel alive as if we are a part of them.

Goodfellas

Goodfellas, of course, continues Scorsese’s signature uses of slow motion and perspective (watch the incredible perspective switch in the Copacabana scene), but he goes for broke in terms of style putting us inside the mind of his main character. In filming three different decades, Scorsese used filming techniques only available during the era in which the movie was set. We so associate history with film that we often imagine the 1950s looking like Leave it to Beaver. Hollywood has so infused our memory that we often imagine and dream in the styles they created. Each decade in the film has its own unique style of expression. In the 1990’s, when we enter the realm of MTV editing, the faster editing pace is used to express the drug induced state of Henry Hill’s mind. Absolutely astonishing.

Silence

Scorsese is known for his use of graphic violence. Taxi Driver almost got an X rating for violence and he decided to desaturate the color of the blood to avoid such a rating. Worried about that in Raging Bull, which has even more blood than Taxi Driver, Scosese decided to shoot the film in black and white; he had other thematic reasons for wanting to shoot in black and white, but this made the decision easier. With all this being said, Scorsese has never used violence as well as he does in Silence. Rather than showing us the violence (a typical thing he would do such as the knife stabbing opening of Goodfellas, or the hand that is completely destroyed by a gun in Taxi Driver, or the explosives placed under fake skin in Raging Bull to cause the blood to literally fly out of his face), Scorsese chooses not to show much of the violence in Silence. He keeps the violence just slightly off screen and uses sound to carry the meaning into our hearts. Just like Rodrigo, we experience the violence second hand, but as a result, we feel the same desire he does to stop it. It’s a much more effective use in this film, which shows Scorsese’s continuing innovation.

The Wolf of Wall Street

One of Scorsese’s longest collaborators has been Thelma Schoonmaker, his editor. I think that one could credit Woody Allen’s casting director, Juliet Taylor, who has cast all of his movies, with at least part of the Allen’s success. The same argument I think can be made with Schoonmaker. Here, Scorsese and his long time editor have their work cut out for them. In an interview, Schoonmaker talks about how the length of the movie The Wolf of Wall Street was the point. Scorsese wanted his audience to feel the excess of Jordan’s life style. He wanted us to feel sick. He wanted us to feel bored and so the repetitive nature and length of the editing only add to the overall effect of the film. No other movie he’s made has been edited quite this way.

Hugo

This may be the closest movie to Scorsese’s heart. Hugo is a celebration of cinema. One of its main characters is one of the earliest pioneers of the artform, George Milles played by Ben Kingsley. Milles was one of the original pioneers of special effects. He pushed cinema to new narrative lengths with films such as “Voyage to the Moon,” where a group of scientists flies to the moon in a bullet. Scorsese, in making Hugo, I think decided to try and make the movie as Milles would have. If Milles had lived in our time, he undoubtedly would have experimented with 3-D filmmaking; so, so does Martin Scorsese. In one of only three films I think to crack the mystery that is 3-D filmmaking and use it for a purpose other than gimmicky, Scorsese uses 3D to create 3-D images on the side as the camera, rather than moving towards the lens, and instead, moves the camera through the space. It’s an extraordinary achievement that adds to the nature of the film itself.

Mike Leigh:

Unlike Scorsese, Mike Leigh is not a director who typically emphasizes the visuals of his films and, certainly technically, doesn’t extend himself too far from his beautiful use of mise-en-scene. There are exceptions such as the use of color in Mr. Turner, but inventive Mike Leigh typically is not. What Mike Leigh does so well is create narratives and characters that break through the artificiality of art and give us life on screen. By doing so, his movies are emotional and sometimes difficult to take. I believe that it is his style of creating a movie that makes these films possible. Mike Leigh rather than beginning with a script, begins with a group of actors and an idea. They spend months improvising in those characters, in those time periods, discovering the true conflict and depth of the situation and then write a script. The result, these actors have lived these characters, the nuances they create play out in films like the way Vera Drake, inhabited so brilliantly by actress Imelda Staunton, lightly waddles showing a woman who has given birth numerous times, to the neurotic hand gestures of Jim Broadbent’s Gilbert; these motions and understandings bring to life a story that is hard to replicate.

Mike’s style could easily go unnoticed and that is a credit to his style, that he disappears so into his work. His style seems to change in ways between one movie and the next. He is not replicating himself. That being said, there are of course similarities in interests to some of his subjects, as well as methods to the way he goes about constructing a narrative.

Since his earliest movies, Naked and Secrets & Lies, he has been interested in the family and relationships, creating stories that involve units rather than individual protagonists. It is impossible for example to say who is the main character from Another Year when both of the husband and wife have equal stakes and story decisions.

Then there are his character studies. Films that analyze and dive into the mind or life of a single individual. Of course, there are supporting casts, but make no mistake, these films really focus on an individual, often giving them breathing room and time alone, making it so, at times, there doesn’t seem to be a narrative; but, we, as the audience, instead seem privy to some aspect of their personal life that we should not be able to see.

Finally, there are his historical pieces. For someone who is so assured with creating characters in the present and making them real, Mike Leigh also has an eye for period, for creating not only a character that is real, but a world of a time since passed whether that be London after World War II in Vera Drake (a character study) or the Savoy Theater of Gilbert and Sullivan in Topsy Turvy. None of these types of movies are isolated in themselves. They are woven together; a film like Topsy Turvy is obviously a historical drama bent on asking how such creative invention and theater work, but, it is also a story of a unit, in this case, a theater company, rather than a family.

Below is a look at the three types of movies that I have outlined above: Mike’s family or relationship stories, his character studies, and his historical period dramas.

Another Year

Another Year has more in common with Mike Leigh’s earlier films Naked and Secrets & Lies than his character studies or his time period films. Another Year lacks a central plot and seems to have a lot in common with Ozu’s films where we meet characters are different seasons of the year, moving through time without regard for its passing. Here, we watch this happily married couple, Tom (Jim Broadbent) and Gerri (Ruth Sheen) go through several seasons in their lives. Moving through different months in their lives, Leigh focuses on the minute details of their relationships: the way they hold each other, the way they can glance at each other and communicate so much without words. Watch how the couple work as a unit in dealing with the problems of their children and their friends. It’s in these dysfunctional relationships that this couple shine as partners.

Vera Drake and Happy-Go-Lucky

Vera Drake could easily be “an issue movie” since it is about a woman who provides abortions to the poor women in London following World War II. The movie does indeed make a point by demonstrating that the rich do not risk the same danger as the poor in seeking illegal abortions. The rich can afford to either pay a doctor, falsify records, or fly the person in need to a place where it is not illegal. But, that is not ultimately the focus of the film. The film narrows in on one person: Vera Drake a saint of a woman who cannot even bring herself to say what she is helping young women do. She simply says, they’re in need. I help. Imelda Staunton disappears into the role and shows how this wonderfully compassionate woman tries to ensure her family is taken care of. Vera must never sit, but rather, always stands, waiting to help someone else. The movie’s character study dives into the complexities of how someone who can be so loving would also be considered a criminal.

A very different movie, Happy-Go-Lucky, is a showcase for Sally Hawkins who plays the main character Poppy. Sally Hawkins is one of our most underappreciated actresses. Here, she plays a character who is so optimistic and positive that she risks being either one-note or a completely unrealistic characterture. However, Leigh and Hawkins ground her character in reality. This is not a facade, but a way of approaching life. Yes, she is also flaky as a result of her “it’s always okay” attitude, but, she does this to deal with her loneliness at 30, unwed, without a path in life. In the film, She is placed against a driving instructor who is supposed to teach her how to take driving seriously, while she tries to show him life needs to be looked at through rose colored glasses. Even when her behavior of being positive becomes a negative, she cannot help herself. This character study is a way of showing a person who has developed a defense to the world around them. Being happy is a way of life for Poppy.

Topsy-Turvy

When it was announced Mike Leigh was making this film, I was surprised. Prior to this, he had mainly done modern family pieces about British identity, so doing a period piece seemed an odd choice. Why I shouldn’t have been surprised is that this movie is about theater and is perhaps the most intelligent film ever made on the subject. Here, we meet Gilbert and Sullivan, a dynamic duo of music and story who have hit mainstream, but have grown static and repetitive in their latest works. Sullivan, considering himself the superior of the two, thinks that Gilbert has long caused his own career to stagnant and dreams of leaving the team to write “serious” music. Sullivan’s “serious” music is not remembered, while their shows are still today. Gilbert is a neurotic man with an eye for detail. Watch how he works with the actors on pronunciation of words so that the rhythm of what he’s written flows. Watch how the actors are portrayed, having known each other and worked together for years. See how they empathize with the older actor, played by Timothy Spall, when his solo is cut from the show; a poor ending to a great career. In the end, the feel of the movie is perfect and Leigh uses his own attention to detail to recreate a period perfectly. He doesn’t leave behind his incredible understanding of character and psychology to do it either. Gilbert is a fascinating study of a man who will never be happy with anything he makes, because nothing is perfect.

Then, there is the film where Mike’s stylistic approach changed. In Mr. Turner, given the subject of his film is a famous painter, he decided to use the camera, the mise-en-scene, the color to suggest how Mr. Turner saw the world and thus created his art. The result is the most visually stunning work of his career where the visuals of the film feel like Turner’s own paintings.

Charlie Kaufman / Spike Jonze:

I decided rather than splitting these two artists and having Charlie credited only with the movies he’s directed on my list (Synecdoche, New York and Anomalisa) and not the films he wrote that Spike Jonze directed (Being John Malkovich and Adaptation) that I would combine these artists. Charlie has written 5 films on my top ten lists as well as directed two of those films: Wrote: Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind as well as wrote and directed: Synecdoche, New York and Anomalisa. Spike Jonze on the other hand directed two of Charlie’s films on my list (Being John Malkovich and Adaptation) but also directed both Where the Wild Things Are and Her.

Kaufman: In a world where there is no originality left, Charlie Kaufman writes original films. Realizing that the final frontier of mankind is not the stars or the ocean, but rather the human mind, Kaufman’s films explore how our mind works in allegorical and whimsical ways. Whether it’s tackling what it’s like to crawl into someone else’s mind or your own mind in Being John Malkovich (the fact that John Cusack’s character is a puppeteer as a profession before he finds the portal into the mind of Malkovich is an amazing piece of symbolism that pairs so well with the puppets in Anomalisa) or tackling what is inspiration and how does it work in Adaptation, or diving into Jim Carey’s mind as he tries to hide the memory of the love of his life from a process that erases memories in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, or building a set that is actually a representation of a human mind in Synechdoche, New York, or creating a world of puppets to demonstrate how isolated we all are, Charlie is always pushing the limits of cinema. From his movies, always expect a really intellectual concept, but one done with real emotion and humor. One of the funniest scenes I can recall is seeing Meryl Streep playing a high Susan Orlean, making a dial tone noise. It is just a joy and amazing that our greatest actress took such a role. But, his films also have such a depth of emotion; whether it’s one of the most frightening endings of all time when John Cusack looks at the woman of his dreams through the eyes of the young girl in whose mind he is trapped or the genuinely moving moment when a fictional Donald Kaufman tells Charlie “you are what you love.” The best screenwriter working, perhaps the greatest ever.

Jonze: Spike Jonze began his directing career in music videos, creating some of the best of our time including Weezer’s incredible video for “Buddy Holly”, taking us back and placing us in the tv show “Happy Days”. His visual sense is incredible. Jonze is the perfect fit for Kaufman’s screenplays because he loves to play with the reality of the films he makes. Not only did he direct two of Kaufman’s films in my top tens (Being John Malkovich and Adaptation), but I also have selected two of his own films: Where the Wild Things Are and Her. Let’s look at these two films to understand why Kaufman and him are a perfect pair.

Where the Wild Things Are and Her are both considered genre films. Where the Wild Things Are is a fantasy adventure while Her is a science fiction film; or so we would believe going into them. Indeed, they do adhere to the genres they are a part of, but their real subject is human psychology. Like Charlie Kaufman’s works, Spike Jonze’s works tend to visualize what our mind creates. In Where the Wild Things Are, Jonze creates a fantasy world that is the imagination of Max. Since Max wants to run as far away from home as possible, Jonze wisely decides to set his home in winter, so that the place he runs to is a desert; completely different from his life. Max feels alone and isolated at home with his sister, who was his best friend, but has grown up, and now, brings her teenage friends to hang out rather than hang out with him. As a result, the Wild Things sleep on a giant pile of each other, showing their closeness and their camaraderie. Within the world, he finds a model of the world (suggesting the child’s idea of creating a world within their own world). But as with all children, if you let them play in their fantasy, the problems they are dealing with surface. His best Wild friend ends up embodying his own anger towards the changing world around him. Similarly in Her, Spike needs to take us into the mind of Joaquin Phoenix as he falls in love with the voice of his phone. Subtetly, using colors and certainly demonstrating a brilliance in the scene where “they have sex”, Spike makes us feel the same as Joaquin. This voice is a person and we too are in love. The relationship feels real even though it is artificial.

Both of these creators explore our mind in ways that most directors don’t. They are a remarkable set of artists to be working at the same time.

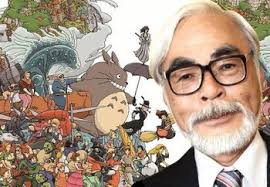

Miyazaki Hayao:

The god of animation. There is a shot in Princess Mononoke where rain starts to fall on a rock, a few drops at a time, then more, and finally the entire rock is covered and now uniformly wet. It is not important persay to the story and hand animating that image takes a great deal of time. But, this is exactly what is so special about Miyazaki’s films. When asked to explain how his animation is different from American animation, he thought about it and then clapped four times. He said that American animation seeks to animate the clap; he seeks to animate the silence between the claps. This is the genius of his films.

In Spirited Away, there is a moment where San waits patiently for a light coming towards her until we realize it is a lamp jumping on it’s own. It arrives and bows to her, before turning and encouraging her to follow it. When they get to the house, the lamp hangs itself up. There was no need to give that lamp personality, emotion, or take the time to walk with it in silence.

In My Neighbor Totoro there is the incredible bus stop scene where Totoro and the two girls wait patiently together in silence. Neither knowing what to say or how to act in front of the other. Finally, offering an umbrella to Totoro, the giant furball is grateful, raising it up to cover himself from the rain. In doing so, he discovers the feeling of drops falling on the umbrella. Fascinated, he jumps and causes a flood of water to come down. These moments bring life to these films; they are real.

Miyazaki has long been a mainstay on my top ten lists as I love animation. From his more “grown up” films (Princess Mononoke and The Wind Rises) to his childhood fantasies (Spirited Away and Ponyo) his films burst at the seams with his wild imagination. The worlds he creates are second to none. In his childhood fantasies, he also imbues them with an innocence that is missing in most stories. Conflict is the basis of all storytelling and yet My Neighbor Totoro moves its narrative not with conflict, but with discovery. His films remind me of the goodness in the world.

By the numbers:

Below is a list of most of the directors who have appeared more than once on my list. The ones in bold will be featured later on a reflection dealing with directors who careers developed during my lifetime.

Martin Scorsese – 6 ((Gangs of New York, The Aviator, The Departed, Hugo, The Wolf of Wallstreet, and Silence)

Kaufman – 5 (Wrote: Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind as well as wrote and directed: Synecdoche, New York and Anomalisa)

Mike Leigh – 5 (Tospy-Turvy, Vera Drake, Happy-Go-Lucky, Another Year, Mr. Turner)

Spike Jones – 4 (Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, Where the Wild Things Are, Her)

David Gordon Green – 4 (All the Real Girls, Undertow, Snow Angels, Joe)

Wes Anderson – 4 (The Royal Tenenbaums, The Fantastic Mr. Fox, Moonrise Kingdom, The Grand Budapest Hotel)

Alfonso Cuaron – 4 (Y Tu Mama Tambien, Children of Men, Gravity, Roma)

Miyazaki – 4 (Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away, Ponyo, The Wind Rises)

Woody Allen – 3 (Anything Else, Midnight in Paris, Blue Jasmine)

Darren Aronofsky – 3 (Requiem for a Dream, The Wrestler, Black Swan)

Ang Lee – 3 (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Brokeback Mountain, Life of Pi)

David Lynch – 3 (The Straight Story, Mulholland Drive, Inland Empire)

Patrick Wang - 3 (The Grief of Others, Bread Factory: Part I, Bread Factory: Part II)

PT Anderson – 2 (Magnolia, There Will be Blood)

Peter Docter – 2 (Up, Inside/Out)

Clint Eastwood – 2 (Million Dollar Baby, Letters from Iwo Jima)

David Fincher – 2 (Zodiac, The Social Network)

John MacDonagh – 2 (The Guard, Calvary)

Kenny Lonergan – 2 (You Can Count on Me, Manchester by the Sea)

Martin McDonagh – 2 (In Bruges, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri)

John Madden – 2 (Shakespeare in Love, Proof)

Terrence Mallik – 2 (The Tree of Life, Knight’s Cup)

Tom McCarthy – 2 (The Visitor, Spotlight)

Sam Mendes – 2 (American Beauty, Skyfall)

Errol Morris – 2 (Fog of War, Wormwood)

Chris Nolan – 2 (The Dark Knight, Dunkirk)

Park – 2 (Oldboy, The Handmaiden)

Alexander Payne – 2 (About Schmidt, Sideways)

Sam Raimi – 2 (Spider-man 2, A Simple Plan)

Steven Spielberg – 2 (Minority Report, Munich)

Spike Lee – 2 (25th Hour, Chi-raq)

Tarantino – 2 (Kill Bill Vol 2, Django Unchained)

Lars Von Trier – 2 (Dancer in the Dark, Manderlay)

Dillon Villeneuve – 2 (Arrival, Blade Runner 2049)

Zhang Yimou – 2 (The Road Home, Coming Home)

Berry Jenkins - 2 (Moonlight, If Beale Street Could Talk)

Ryan Coogler - 2 (Fruitvale Station, Black Panther)

Debra Granik - 2 (Winter’s Bone, Leave No Trace)