Top Ten Animated Films with Guest Writer Tucker Meijer: #1

Finally, we are here. Below is Tucker and my selections for the best animated film of all time. As always, if you want to read the introduction from Tucker and myself, please go to our choices for the #10 best animated film. Before we get to our selection for the best film, here is a recap of our lists:

#10: Tucker’s selection: Inside Out / Jeremy’s selection: The Iron Giant

#9: Tucker’s selection: Nausicaa: Valley of the Wind / Jeremy’s selection: The Wind Rises

#8: Tucker’s selection: Spider-man: Into the Spider-verse / Jeremy’s selection: Ratatouille

#7 Tucker’s selection: Up / Jeremy’s Selection: Anomalisa

#6: Tucker’s selection: Spirited Away / Jeremy’s selection: Inside Out

#5 Tucker’s selection: Toy Story 3 / Jeremy’s selection: Spirited Away

#4: Tucker’s selection: The Iron Giant / Jeremy’s selection: TIE: The Little Mermaid and The Hunchback of Notre Dame

#3: Tucker’s selection: Mulan / Jeremy’s selection: Princess Mononoke

#2: Tucker’s selection: Akira / Jeremy’s selection: Pinocchio

Now without further ado, our choices:

Tucker’s #1: The Incredibles

I’m going to begin this review with an acknowledgement that The Incredibles is an unconventional choice for the best animated film of all time. By the time the film premiered in 2004, Pixar had already released a slew of critical darlings like Toy Story, Toy Story 2 and Finding Nemo. The most common place for The Incredibles in critics’ roundups of Pixar movies is the upper middle echelon; on these lists, it’s pretty good, but doesn’t quite reach the same level as Up, Inside Out and Toy Story 2 or 3. All of this is to say that I understand that I have my work cut out for me in trying to convince everyone that, in my opinion, The Incredibles is the best animated movie of all time. But here goes nothing!

The Incredibles opens in a surprisingly quiet way. Even before the longish sequence of Mr. Incredible/Bob Parr saving various people (and one cat) throughout the day before rushing to his wedding with Elastagirl/Helen Parr, a few of the major characters appear as talking heads on a TV news segment. Mr. Incredible, Elastagirl and Frozone tell the camera (and, ostensibly, to us) about how all supers have a secret identity, setting up a major theme in the movie about the things that are kept secret in a family and to the world. The sequence ends in irony: Mr. Incredible explains how he sometimes wants a simple life, to settle down and raise and family and Elastigirl emphatically argues the opposite as the screen fades to black (a major conflict in the story is that Bob wants to return to crime fighting. Helen does not).

In the occasionally chaotic film that follows the opening, the TV sequence is a perfect encapsulation of the fact that the most powerful moments in the film are these quieter moments, away from all of the action. In another later scene, Helen tries to explain the perilous situation that they’re in to Dash and Violet. It’s an incredible moment where Helen attempts to navigate the tension of being incredibly real with her children, explaining that they will be killed if they are found, and also wanting to shield them from the evils of the world. In another later scene, after the whole family has been captured, Bob attempts to bumble around an apology. Helen is listening intently, while Violet creates a force field around herself and floats down from their prison. This moment is imbued with humor and heart in the way families often are.

This is truly where The Incredibles shines. All of the superpowers, all of the action: these are vehicles to explore a very real familial relationship (albeit a straight, white, upper middle class one), where personalities compete and the day-to-day experience is filled with as much excitement as the running from the bad guys. The character traits are physicalized in their super powers: Bob’s strength from his outward appearance of stoicism, Helen’s elasticity from her ability to bend in many different directions to care for her kids, Violet’s invisibility and force fields from her shyness and struggle to open up and Dash’s speed from his boundless energy. Yes, it’s obvious. But that’s part of the point. Superpowers don’t necessarily make us superheroes. Our personalities and our strengths are the parts of us that make us supers.

These are the big things that make The Incredibles simultaneously relate-able, uplifting and empowering, but there are the smaller nitty-gritty components along the way that contribute to its greatness. There is the strength of the ensemble characters: Frozone and Edna Mode are endlessly quotable (“Where’s my supersuit??” / “No capes!”) and contribute to the narrative beyond being the funny side characters. The exact time period is left ambiguous to contribute to a sense of timelessness (after all, this is a story about family, not about a moment in time). Syndrome is a wonderfully three-dimensional character whose transition to villain makes sense (the person he looked up to and idolized spurned him multiple times - who wouldn’t be mad?). The setting oscillates between being rich and vibrant on the island to dull and washed out in Bob’s office to contrast the two competing forces. These things are nailed with precision and continue to make The Incredibles an enjoyable and watchable film.

Is The Incredibles a perfect movie? No. But to me, it comes pretty darn close. At times the movie is messy and chaotic. But then again, so is family. There’s a whole lot of love but a whole lot of conflict and strife as well. I have been trying to find a movie that handles the complexity of family dynamics with the same tenderness of The Incredibles and have yet to find one (The Incredibles 2 doesn’t even come close). This speaks to the greatness of this film and makes it one of the best animated films of all time.

At one point in the film, Syndrome tells an imprisoned Bob, “And if everyone’s super, no one will be.” By the end of the film, this point will be disproven. Everyone is super in some way and that just makes the world more vibrant and colory. That’s pretty incredible if you ask me.

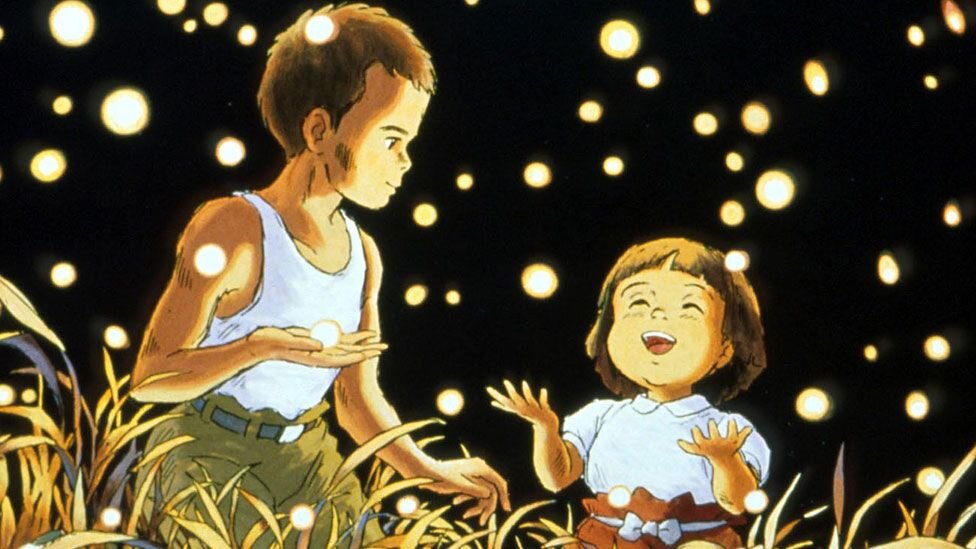

Jeremy’s #1: Grave of the Fireflies

There are some movies that stay with you, seared into your soul. Movies that you will never forget; that become a part of who you are. For me, Grave of the Fireflies is one of those films. Every time I have seen it, I have cried uncontrollable tears by the end at the grave injustices in the world and the pain and torment that can be wrecked upon the innocent. I remember when we watched it for a class in college. My professor asked us to come in on a Sunday to see a movie. He surprised us with this film at 10am on a Sunday morning. I asked if I could leave before we began. He said no. By the time we were done, a classmate of mine, Adam who was a thirty-year-old grad student with a young daughter, was so affected by this film that he was inconsolable. Grave of the Fireflies may not be a film I reach for often, but I cannot understate its power.

Grave of the Fireflies belongs in the pantheon of great animated films, but also, great anti-war films. It should be mentioned in the same breath as All Quiet on the Western Front, Letters from Iwo Jima, Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory, Bridge on the River Kwai, both Terrence Mallick’s The Thin Red Line and Hidden Life, Grand Illusion, and Oliver Stone’s Platoon and Born on the Fourth of July. Unlike many of these movies (save Born on the Fourth of July and A Hidden Life), this film does not suffer from Francios Truffaut’s famous insight that no movie can be anti-war because the visuals of war are inherently exciting. Grave of the Fireflies removes itself from the battlefield and focuses on the lives of two children who are trying to survive the war. At first, they try to survive the loss of their mother, then the cruel indifference of their family, and finally the reality of a war-ravaged country. The film better demonstrates that tagline from Stone’s Platoon than his film did: “The first casualty of war is innocence.”

Grave of the Fireflies is based on a short story by author Akiyuki Nosaka who lost one sister to sickness before the bombing of Kobe in 1945 which took his father’s life. After the bombing, he tried to care for his younger sister who died of malnutrition. The short story was written by Nosaka as an apology to his sister whom he felt he failed and allowed to die. These deep emotions seethe from this story. Adapted into a film, Isao Takahata saw in the young male protagonist, Seita, a modern young man capable of expressing himself emotionally and not the type of young boy who would have lived during the war. Japanese men and boys during that time were even more emotionally confined than men today. Culturally, boys are supposed to “man up” and that is still unfortunately the norm, but in WWII Japan, this was taken to an extreme. Nosaka agreed with Isao’s insight, saying that he saw Seita as everything he wasn’t. In real life, when Nosaka found food, he ate it, rather than giving it all to his sister as Seita did. Seita stands for the hope in our world, and yet, even with that hope, he fails in saving his sister or himself.

The movie’s plot is extremely simple; disturbingly so. The two children lose their mother in the beginning of the film to firebombs. These bombs they nickname fireflies because they light up the night sky. There will be a juxtaposition that is one of the most beautiful scenes in all of cinema when the two of them stumble upon an entire forest filled with actual fireflies. Their beauty and joyfulness that they evoke stand in direct opposition to the bombs that fall from the sky.

After losing their mother, Seita takes it upon himself to be the sole caregiver for Setsuko. He is a mere teenager, 11 to 13 years old, just coming into the understanding of the concept of adulthood and being a “man”. His sister is 4 years old; the perfect age to symbolize innocence. At first, Seita makes the adult decision to seek out their Aunt for aid. Unfortunately, war times are hard. Rationing has left little food for the general public and his Aunt balks at two more mouths to feed. Eventually, deciding that it is better for him to care for his sister alone, they leave and make their way into the countryside.

In the countryside, Seita and Setsuko find isolation from the war and with that a revival of their imaginations and innocence… at least for a while. While living in the countryside, they begin to behave as kids again in an imaginary heaven. It is a joyous time and for an instant, you forget the beginning of the film, where Seita is laying in a subway dying of starvation when he begins to tell this story. Forgetting that image, you feel like they might be able to survive the horrors the world has put upon them. In one instance, Setsuko plays in mud. Mud, a box, a stick, these are the things that childhood imagination brings to life. You could be at the finest tea palace in England, serving tea with the teapot you made from mud. But then, reality returns.

The sequences where they begin to become hungry, then desperate, then starving are some of the most difficult scenes to watch that I have ever seen. Even though the film is animated, it treats these sequences with a documentary intensity to detail. When Seita returns to their cave without food after having begged and pleaded with those who could help, he even thinks about stealing, he finds Setsuko so hungry that she is delirious. His little sister is sitting on the ground eating the mud “food” she had made in her make-believe game. This is the reality of our world. One in which through the courses of conflict and international fighting, we forget the true victims of war: the innocent. One of the hardest realizations is not simply that they are dying, but that their imagination cannot save them. In such circumstances, we not only kill the body, but we also kill the soul.

Nosaka has spoken about how Grave of the Fireflies is a double suicide story. In Japan, there is a history and tradition of double suicide narratives, especially in theater. In these stories, the two lovers (although it does not have to be romantic, it can be familial) realize that they will be separated by death decide to dwell on the good times. In doing so, they want to return to them and force themselves back together by each ending the others life. They will be together in those happy memories in the next world. The film returns at the end of Grave of the Fireflies to Seita dying on a subway platform, ignored by the world. For Nosaka, this is wish that he can be together with this sister again. In giving us this story, he pours his soul, his failed responsibility to save his sister into a narrative that gives her life again and reunites him with her. Even in the darkest hour, the narrative itself, while heartbreaking and depressing, is a relief for the author who needed such a release. We are blessed that he had the strength and courage to share it with all of us.

When Grave of the Fireflies was set to be released in America, Walt Disney Pictures balked at releasing it. America so often does not consider animation an adult medium, but merely for kids. Grave of the Fireflies is specifically not for children. Some have dubbed it “the Schindler’s List of animation.” Perhaps, in impact, it is. Realizing Disney was not going to release the movie, Miyazaki made a fascinating demand. He had just finished one of his masterpieces My Neighbor Totoro and he refused to release it unless it was part of a double feature: Grave of the Fireflies and My Neighbor Totoro. By doing so, he forced Disney to release Grave of the Fireflies in America. These two films seen back to back is one of the greatest double features in all of cinema. Depending on the order you watch it, it changes your understanding of the world. If you watch My Neighbor Totoro first, you truly do believe in the middle of Grave of the Fireflies that their imagination could save them, before watching them starve. It is a shattering of childhood innocence in the face of human evil, war. In this order, the pain of reality destroys everything that is contained in childhood wonder. Or, you could watch Grave of the Fireflies first and then My Neighbor Totoro. In this order, the films restore your faith in human spirit after it has been challenged. I prefer the second option.

With that, I would like to thank Tucker for forcing me to write regularly for the past couple weeks. Sharing his choices and commenting on them has been a joy.

As a postscript, here would be my runner’s up from 11-20:

#11 Beauty and the Beast

#12 Spider-man: Into the Spider-verse

#13 Fantasia

#14 Snow White and the Seven Dwarves

#15 Bambi

#16 The Tale of Princess Kaguya

#17 My Neighbor Totoro

#18 Ghost in the Shell

#19 Toy Story 2

#20 Nightmare Before Christmas